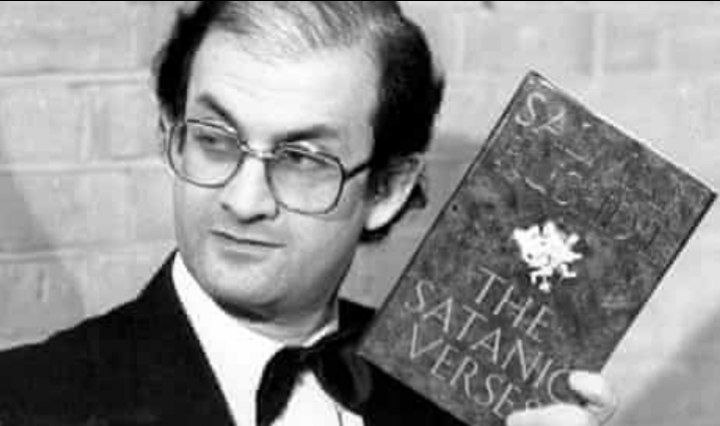

Salman Rushdie’s 1988 book has won him more enemies as well as friends!

The Satanic Verses made him a target of extreme Islamists who have had a bounty over his head for all those years.

The novel is primarily about two Indians of Muslim background (but indifferent faith), both of whom, in the opening chapter, are falling from the sky over England as their plane was just blown up.

Gibreel Farishta and Saladin Chamcha spend the entire novel as magnetic poles, opposites drawing one another closer. After surviving their fall from the sky, Saladin becomes a goat, while Gibreel becomes (at least in his own mind) the Archangel Gabriel. Gibreel descends into madness; Saladin gets beaten up by the cops (his transformation into an animal is both literal, in this book of “magical realism,” and metaphorical, as a symbol of post-colonial racism).

Their life stories, their loves, and their careers span the entire novel, from their upbringing in India to Gibreel Farishta’s success as a Bollywood star and Saladin Chamcha’s career as a voice actor. But after surviving their plane disaster, Saladin has become a devilish adversary to Gibreel’s angelic persona. They are bound together by jealousy, disaster, shared ex-patriate experiences, and madness.

READ: Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses Shoots Up Amazon Best-Seller List in Wake of Attack

I found the book interesting but meandering. Rushdie seemed to be trying to do too much. He’s imaginative and funny and his words are deeply layered – this is quite a literary novel with flourishes of fantasy, humor, and allegory.

Anti-Islam?

The stories of the two protagonists, Gibreel Farishta and Saladin Chamcha, are interspersed with dream sequences that retell the life of Mohammad.

Muslims are notoriously prickly about using the Prophet as a character of any sort, but what really seemed to do it for Rushdie were three parts in particular:

- The “Satanic Verses” for which the novel is named, which turn out to be based on actual Islamic apocryphal stories in which Mohammad supposedly endorsed the existence of three pre-Islamic goddesses, before retracting his words.

- In one dream sequence, a satirical poet who is an adversary of Mohammad hides in a brothel, where the prostitutes assume the personnas of Mohammad’s wives.

- Most likely what really pissed off the Ayatollah, there is another dream sequence in which the Ayatollah himself is unflatteringly portrayed in the character of a nameless “Imam” living in Paris

Salman Rushdie is a storyteller of prodigious powers, able to conjure up whole geographies, causalities, climates, creatures, customs, out of thin air. Yet, in the end, what have we? As a display of narrative energy and wealth of invention, ”The Satanic Verses” is impressive. As a sustained exploration of the human condition, it flies apart into delirium as ”pilgrimage, prophet, adversary merge, fade into mists, emerge.” Does it require so much fantasia and fanfare to remind us that good and evil are deeply, subtly intermixed in humankind? And why then trouble ourselves about it? In a world of mirages, of dreams within dreams, what is death and what is life, and why should it matter to choose between them?

For, often, the result of all this high-wire virtuosity is a dulling of affect, much like the blurring created by rapid hopping between channels on television: nothing seems quite real. Mr. Rushdie himself, an astute observer of the effects of fast-forwarding and remote-control devices on the way we perceive the world, takes careful note of the channel-hopping phenomenon, observing that ”all the set’s emissions, commercials, murders, game-shows, the thousand and one varying joys and terrors of the real and the imagined” begin to acquire ”an equal weight.”

But, of course, they aren’t of equal weight, and after closing ”The Satanic Verses” the real strengths of the book assert themselves. What finally lingers, what lives most vibrantly, for this reader, are the scenes that are grounded – the places where magic doesn’t overwhelm the realism – the moments when Mr. Rushdie looks ”history in the eye.” They are scenes of expatriation, of political exile, and the story of Chamcha’s patrimony – indeed, the whole, nearly complete novel-within-the-novel concerning Chamcha and his father.

The reviews are the works of inverarity.livejournal.com and The New York Times.

Personally, I started reading the book back in 2018, but I found the book hard to comprehend.